Photography

Processing with intent

Understanding what you’re trying to achieve with an image before you start moving sliders and applying presets

I recently came across an old blog post by Nigel Cooke, cached in my RSS reader (yes, I still use RSS) that really resonated with me.

Nigel’s post, sadly no longer available as he’s shifted focus to travel and shut down his old site, begins:

“I used to think that I was being clever by having a large back catalogue of un-edited images in my possession. Something for a rainy day I’d tell myself. Well I’m starting to realise that this approach may actually have an unseen negative side which is potentially diluting the potential of my work.”

Nigel goes on to talk about processing with intent, mentioning Bruce Percy—a photographer I was unaware of but am now digging into more—and how he felt he’d fallen into a pattern of processing his images in a rather random fashion, mixing themes and moods to the detriment of the finished images.

The problems raised

The two concerns raised by Nigel as I read his post were:

- Processing images in random order can lead to editing two images with totally different moods and tones at the same time, with all the drawbacks such context-switching can entail like preventing getting into a flow state on one theme. The overall quality of all images thus reduces.

- The dip-in-and-out approach means many images languish in his ‘for processing’ collection so by the time he comes to edit them, any intent he had at time of capture is long lost, so Nigel felt he may just have been “putting lipstick on a hog”.

Taking stock

For a few years now I’ve structured my photo management and processing workflow along the lines of that proposed by Trey Ratcliff in his Lightroom Workflow tutorial, which advocates just such a dip-in-dip-out approach to post-processing.

As such, Nigel’s post did make me sit up and think about whether I’m suffering from a similar lack of intent in my post-processing. I think I probably am.

Current process

Born out of his publishing style of sharing one photo every day, Ratcliff is less worried about processing sets of images than the individual photographs that inspire him on a given day. As such, he cherry-picks an image or two to work on at a time in Lightroom, not worrying about how many are still unprocessed or what order they are addressed in. The approach lets Trey focus on the small number of images that inspire him at any one time rather than feel obliged to work through a whole set in order.

This process obviously doesn’t suit everyone—very few people manage to publish close to a photograph each day—but I really liked some of the foundational Lightroom workflow things he set up as a result of his workflow. As someone with way more images to process than time available, the change in mindset away from feeling a need to get through a whole set in one go really freed me up and has also led to me more often rediscovering old gems from years earlier.

Processing with intent

Assuming processing with intent is a good thing (I think it is), I had two questions for myself: am I processing with intent? If not, is it my workflow that’s the cause?

Am I processing with intent?

In answer to this first question, my honest answer probably has to be no; certainly not always. It’s something I have definitely got better at with experience but similar to Nigel, I still have the tendency to open an image that’s caught my attention and begin moving sliders around before really thinking about the end result I want to aim for.

A simple but common example of this is my tendency to immediately apply one of Fujifilm’s excellent film presets as a first step on any image, then maybe cycle through them until one ‘looks right’.

Is the workflow the problem?

In small part yes, but not really.

Picking images out one or two at a time can indeed lead to a lack of focus and Nigel’s point about the time between taking an image with intent and processing it losing that intent is a good one.

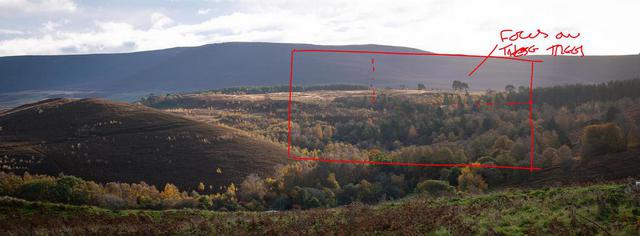

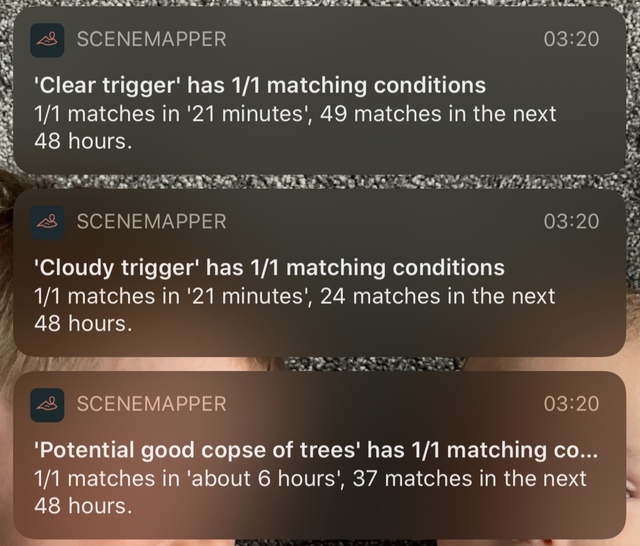

As I’ve worked on SceneMapper, note-taking has been a key element and it’s really driven home to me how much Lightroom could do with note-taking and markup (as in, marking up an image rather than markup languages like HTML/Markdown) functionality.

Really though, the problem is me.

Processes can certainly help steer you in a direction or act as anchor reminders but my career in user experience (UX) has taught me that no process or tool works its best without doing the hard work to get the people involved fully bought-in.

My innate style of photography leans much more to the intuitive: something catches my eye and I photograph it. I have to force myself to think more deliberately about a composition.

Over the years, I’ve tried to work the scene more—Scott Kelby’s ‘Crush the Composition’ talk on this theme at the Google+ Conference years back is still great though no longer officially published online—but I still default to a more run-and-gun style. With a day job and young family, I get so few opportunities for full-on photography days it’s hard for me to slow down and focus on just a few compositions on the rare days I can get out.

So I end up trying to cover as much ground as I can: shooting everything that catches my eye and not prioritising.

On the one hand, it means I always end up with a few “If I’d just taken more time on this scene!” images. On the other, some of my favourite images I’ve ever taken were totally intuitive, (sometimes even literally) from-the-hip shots that capture a moment.

Two stages of intent

Which may be a good time to think about what it means to process with intent.

For me, there are at least two stages of intent: when you capture an image with the camera and, later, when you come to do any post-processing on it.

Image capture

At time of capture, the common advice is to spend time working the scene and also thinking about what processing you’ll need to do to get the finished image you see in your mind’s eye. This becomes particularly important with things like panoramas where it’s so easy to miss a corner or two if you’re not really focused on your desired composition.

Time is a key factor here, and for some types of image you simply can’t stop to find the perfect composition and bracket exposures or focus because you know you might need it in the edit. Sometimes photography is an in-the-moment, reactive pursuit.

Event/sports photography, street photography, travel photography; all of these can make it hard-to-impossible to regularly take the kind of time over an individual image that a landscape photographer typically would.

But that doesn’t mean you can’t have intent. Intent can knowing the kinds of image you’re looking for. A street photographer like Joshua K. Jackson captures some amazing fleeting moments, but we shouldn’t pretend he didn’t have intent. There are clear themes to his work and he puts in hour upon hour pacing the streets of London, getting to know individual streets to give himself the best possible chance of capturing the kinds of image he wants. Sean Tucker made a good video with Josh on Josh’s approach.

Post-processing

The other main opportunity for intent is after the pixels have all been captured and you come to post-process or edit a photograph.

At this point, hopefully yes, you already have an intent for the image that you’re still settled on and can work on figuring out how to execute it.

Alternatively, opinions can change; seeing an image on your computer screen can ignite new ideas and possibilities or simply trigger different emotions in memory versus experience at the time. Maybe the image was an opportunistic one.

At this point, you can appraise the image anew. What does it mean to you now? How does it make you feel? Work on conveying that feeling in the processing. If processing is even necessary. Another trap I know I fall into and struggle to stop is the need to process every image, even if I look at the original file and love it as it is.

Either way, before moving a slider or applying a preset the idea is to slow down and think about where you want to end up with a photograph. As a designer, a key principle I follow is to not begin designing a solution unless I know the problem I should be solving, the hypothesis I’m trying to prove or the message I need to convey.

We’re all our own worst clients though, and it can be so much harder to get a good brief from our own minds than from a client/boss/stakeholder.

Nonetheless, we should still try.

Some (New Year’s) resolutions

As it happens, it’s New Year’s Eve and the traditional time for setting resolutions. I certainly hope these will be longer-lived than most New Year’s resolutions, but here we go:

Focus more on intent in the field

The obvious one, but always a good reminder. When a composition really shows a lot of promise—whether it be that nagging feeling at the back of your mind as something catches the eye or something more conscious—I need to recognise it, slow down and work the scene.

Think about composition: foreground, mid ground, background; framing; contrast; ‘border patrol’; dynamic range and contrast. All the details that could push from a good image to a great one.

… but don’t lose the intuitive stuff

At the same time, this won’t work for me if I try to apply it to every image I take.

I’m no Thomas Heaton or Ben Horne, not even taking the camera out of my bag until I’m happy I’ve found a good base composition, and I don’t think it will help me by trying to be. I love taking pictures and I still want to photograph whatever interests me, with the small adjustments of working a little harder at spotting the times when I should slow down. Each person is different, so don’t follow a process unless it works for you.

… or the fun

A reiteration of the previous point, but I love photography because it’s fun. I go through the world spotting interesting compositions and I enjoy trying to capture them. No process should remove your enjoyment of photography, so if it stops being enjoyable, maybe go back to the previous approach or try a new one.

Plan more

I’ve been working away building my location scouting app, SceneMapper, for over a year now. Much as I intend to release it publicly, at root it’s a tool I’m building for myself to solve some of my own problems and one of those is tracking and remembering to go back to good compositions.

With a good plan and a pre-scouted scene, it’s a lot easier to convince myself to stay longer at a scene to make it work in the right conditions.

Make notes

Along similar lines and part of the core of SceneMapper is note-taking: encouraging intent for a scene and writing it down for later reference. SceneMapper’s focus is location scouting but there’s nothing stopping it being used to make notes about scenes I’ve made ‘final’ captures of.

This is something I’ve already done for film photography with light metering apps that also let you log reference images and notes in place of exif data, so I’ll start using SceneMapper for the same and see both if it works and if I decide to add specific features to enable such a process.

The thing I’d really, really love though is for Lightroom to support both long-form note-taking linked to an image as well as the ability to draw over an image, marking up like you would a contact sheet so that you have toggle-able reminders of your intent for a composition.

Asynchronous processing, mostly

Less a new resolution than a re-affirming that I’m happy with my core photo management workflow. I’ll write a more focused article about my photo management workflow at some point, but my basic approach is to do a quick run through newly-imported images flagging any with promise. I have a smart collection to list all flagged, un-processed images and then normal collections for in-processing and processed images (with sub-collections I won’t go into here).

This works mostly well for me and I don’t see a reason to change it. I still do work through a specific set or session together when it makes sense—for more of a photo story or where I have a particular theme in mind—but it’s on an as-appropriate basis.

A final note on ‘async processing’

While the resolutions above feel like a conclusion to what has become a rather long essay, I want to make note of a few key benefits I get from processing images out of order:

- Inspiration. I often just browse around my selects collection looking for an image that strikes me. Doing this means I can pick up an image that gets the creative juices flowing in whatever mood I’m in at the time rather than force myself to process images I might not be bothered about at the time, just because they’re my most recent, or next in a queue.

- Hidden gems. Another benefit of the big-bucket-of-selects approach is that I regularly re-find old images, often years old like the Yellowstone image I came back to a decade after capturing, that I might not have been keen on at the time but spot potential in now.

- Allowing images to settle. While my main principle in processing is to try and convey the feelings I had in the scene at the time (the best way to define intent for me), it can also be good to give images time to settle. Sometimes we can get over-excited about a scene or a processing approach in the moment and a little distance can help assess an image on its own merits, away from personal memories that other viewers won’t share.

- Removing pressure. Even when I work through a set of images together, unless there’s a specific deadline (i.e. client, or event) I don’t feel the need to wait until every image is finished before sharing one anymore. There’s a set of images from Knole that I adore and did a core pass all together in order to maintain a colour theme, but while most are still sitting in my in-progress collection as not quite done yet, I’ve already shared a couple of photos from the set.

And there, I’ll stop. Well done (I think?) if you got this far through my ramblings on intent and workflow.